You have probably heard something about the way the chile peppers’ “heat” functions, with capsaicin (or really, different capsaicinoids) ‘exciting’ the nerve cells that are really responsible for feeling hot temperatures. Thus, the burning sensation.

Get too much chilli all at once, and it can wreak havoc on the circulatory system, making it start up emergency protocols and, at worst, get the person to collapse.

Get a fitting dose, and it’s a sensation that we humans tend to learn to like. And with use over extended periods, these pain receptors get depleted, so that they can’t fire quite as much. It’s how one gets used to eating chilli, but also how capsaicin batches help against the pain of rheumatism and the like.

Having a pain subside sounds good, but having nerve receptors put out of order sounds like it could be dangerous… except that there is at least one way it is not, apparently – and it is a way that is related to the chilli.

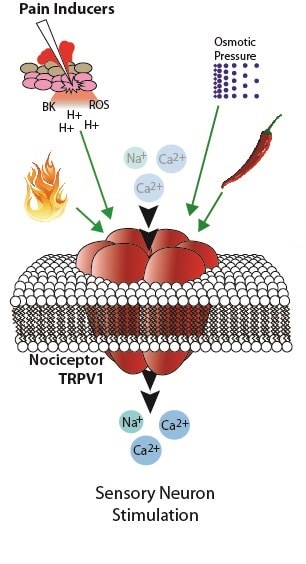

The receptor responsible for feeling (extremely) high temperatures and pain is called TRPV1, and it has a fascinating dual purpose: It is also found in nerves around the pancreas, which it influences. Mice without that receptor feel less pain – and they do not get diabetes even when their diets should make them do so as they age, and they live considerably longer than ‘normal’ mice, to boot.

Recent research (see details below) has found the chemical-neurosensory pathway responsible, which leads to a more youthful metabolic profile, e.g. in a better reaction to glucose at older age (among mice, again). Apparently, having the TRPV1 receptors blocked results in a cascade of factors which give them a longer healthy life, which in turn has further knock-on effects to the point where they don’t just live longer, even their cognitive functioning remains better.

Interestingly for us lovers of the chilli, the TRPV1 receptors cannot only be knocked out genetically (for which the individual has to be born that way, like those in the strain of mice used in the study), they can also be knocked out by capsaicin.

Now, studies in mice and with the application of capsaicin are not exactly the same as results with people eating lots of chilli. However, “[t]he pharmacological manipulation of TRPV1 … might not only be useful for pain but also to improve glucose homeostasis and aging. Consistent with this idea, diets rich in capsaicin, which can over stimulate TRPV1 neurons and cause their death, have long been linked to lower incidents of diabetes and metabolic dysregulation in humans (Westerterp-Plantenga et al., 2005),” as the study authors conclude.

The study in question, if you are in a mood to delve deeply (very deeply) into cell biology, is:

Céline E. Riera, Mark O. Huising, Patricia Follett, Mathias Leblanc, Jonathan Halloran, Roger Van Andel, Carlos Daniel de Magalhaes Filho, Carsten Merkwirth, and Andrew Dillin. (2014). TRPV1 Pain Receptors Regulate Longevity and Metabolism by Neuropeptide Signaling. Cell 157, 1023–1036, May 22, 2014.

The study quoted in their conclusion is:

Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S., Smeets, A., and Lejeune, M.P.G. (2005). Sensory and gastrointestinal satiety effects of capsaicin on food intake. International Journal of Obesity 29, 682–688.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.